Positions of Power

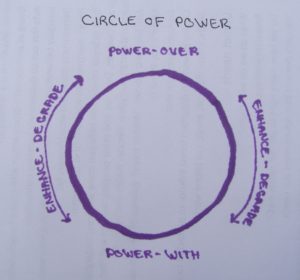

I’ve written before about two positions of power: Power-over (maintaining or creating power inequality) and power-with (maintaining equal power). I’ve thought of this as a complete dichotomy, an either/or lens through which I look at all interactions and relationships, both mine and those around me. Lately, though, I’ve seen two other dimensions in the way we manage power. We are agents of power enhancement or power degradation.

Power enhancement and power degradation are the states between power-over and power-with. If we seek to steal the power of others, we begin by sabotaging cooperation, negotiation and equal access to resources — all those things that create communities based in power-with. If our sabotage is successful, power degradation begins. We don’t have complete power-over, not yet, but we are beginning to break down independence, self-sufficiency and the boundaries of others. We are actively working behind the scenes, slowly and subtly corrupting power wherever we can. We might, at this point, have a change of heart and begin fostering behaviors and situations that recreate and enhance power-with, or we might continue with our goal of power-over. Once our goal is attained, we can cease to lurk in the shadows (or under our sheepskin) and come into the spotlight, flushed and triumphant, bloated with stolen power and proud of it.

On the other hand, if we seek to empower others who have been embedded in a power-over dynamic, we begin by managing our own power in such a way that we enhance the power of the disempowered and degrade the power of those maintaining or creating a power-over status quo. Ideally, we don’t give our power away, because that’s a finite resource and leads to burnout and exhaustion. A better way is to use our power to teach, to lead, to support, to legislate and to generally become the wind beneath someone else’s wings. In other words, we appropriately invest our power into teaching others how to discover, reclaim, maintain and manage their own.

An abused child or woman is not going to know how to take care of themselves and function, even if their abuser is magically whisked away. They have to learn. Actually, first they have to unlearn what they already know — all the coping mechanisms that kept them alive in their situation but won’t work well in the wider world — and then they have to learn new skills and behaviors. That takes time, appropriate support from power enhancers and protection from power degraders, at least temporarily, while the victims of power-over learn how to find and reclaim their own power.

The people who live and embody these two intermediate positions of power, enhancers and degraders, are my people — the caregivers. We are the parents and the teachers; the mentors, spiritual leaders, coaches, medical professionals and volunteers who work at shelters, missions, soup kitchens, and out of tents in far-flung places. Interestingly, most of these folks once came from the exterminated middle class. Also interestingly, we see frequent headlines about how some people in this group misuse their position of power and authority in the guise of “helping” others. Shielded by the mask of a power enhancer, they act as power degraders, abusing and exploiting others unchecked, sometimes for decades.

Power enhancement and degradation are not black/white good/bad positions. Many grassroots organizations seek to degrade power in an effort to address our power-over culture and help others reclaim their rightful power. You might say their agenda is to equalize power. The Southern Poverty Law Center is an excellent example. As parents, we might hope to work as power enhancers for our children. As resistance volunteers, we might work against organizations supporting inequality.

It’s important to note our culture doesn’t financially support people in these positions of power particularly well. Teachers strike for better pay. Coaches lay down their lives in bullet-riddled school hallways. Nurses and doctors are vulnerable to addiction, burnout and fractured relationships. Ditto police and firefighters. Compassion fatigue is epidemic. None of these people are millionaires, and some are becoming homeless in places like California as the cost of housing skyrockets. I also note how many of these positions are filled by volunteers. I myself did volunteer fire and rescue work for years, and then animal rescue work and hospice. Red Cross depends on its volunteers. Many healthcare facilities and schools rely heavily on volunteers, as well as sports teams, churches and countless human rights organizations.

Yet it seems to me power enhancers and power degraders are the most important people in our communities. They have the ability to lift others up into integrity and excellence or destroy them. They shape our health, the way we learn and think (or not, sadly), and our spiritual wellness. We trust them with our children, our souls, our secrets and our lives. When they stumble, burn out, fail or waver, we roar with fury, demand justice and retribution, riot and demonstrate, never considering we are the ones who put them in such dangerous, risky, heartbreaking and impossible positions in the first place. We place them on the front lines, put them under constant public scrutiny and pressure and make them responsible for understanding and fixing our increasingly unequal and dysfunctional social power dynamics.

Consider what a professional athlete gets paid, or an entertainer, or a “successful” politician. Compare that to what your children’s teachers are paid, or your local police or fire people, or your nurse practioner or the local softball coach or scout leader. Who has more direct influence in your life and well-being? Who will come help you in the middle of the night, organize community support or assist you with wedding or funeral arrangements?

Here is a graphic demonstrating the circle of power. (Please take a moment to notice the cutting-edge high tech used to generate this graphic. Impressive, yes?) Currently, a power-over dynamic is running the show, and it lies directly across the circle from power-with. We each occupy a place or places along the circle of power, and those places are dynamic and fluid, depending on the daily and even hourly choices we make. Some people spend most of their lives trying to equalize power between people while others work tirelessly to create and maintain unequal power. We all, whether consciously or not, behave in ways that degrade or enhance our own power and the power of others.

Nobody teaches us about power. Not our parents or schools, and certainly not the media. Yet our inherent rightful power and our need to manage it appropriately and effectively transcends ability level, age, race, sex or socioeconomics. Individual power is apolitical. We all can take the same class, if only we can find teachers.

The problem is, there is no class and our best teachers are exhausted, demoralized, underpaid, underappreciated, overworked and drowning in a crippled education system while others are busy exploiting their positions in order to degrade the power of their students and colleagues. Even if some of the former know something about power management, they’re not in a position to teach anyone else about it. Power management and emotional intelligence skills (which are inextricably intertwined) are not going to show up on a standardized test or entrance exam.

We don’t know how to manage and maintain our power. We haven’t learned it and we can’t teach it. Yet we expect those people who support, protect and serve our communities, all those people who take intermediate roles of power enhancers and degraders, to remain uncorrupted and infallible and spotlessly kind, compassionate, moral, ethical, and just plain GOOD. We give them power and authority blindly, because we can’t recognize appropriate power management from inappropriate either, and expect them to figure it out and do the right thing. We sure as hell don’t know what to do! When that doesn’t happen, we’re angry and we look around for someone to blame, someone or something to scapegoat.

How can we expect things to get better if we don’t make some changes?

I suggest we must begin at the beginning, at the foundations, with our children, which means a new paradigm of parenting. Every single adult coming into meaningful contact with a child must be reeducated about the continuum concept and connection parenting. Children need appropriate connection and bonding throughout childhood. If that happens, they learn emotional intelligence and become secure, confident, curious, joyful people who practice power-with as a matter of course, because their own power has never been corrupted or coerced.

How do we freeze everyone in their tracks, wipe their data banks clean and overwrite with better information? How can meaningful change take place if we don’t?

Don’t ask me. I can think about it and write about it, but I have no idea how to tackle such an overwhelmingly impossible task, even if everyone would consent to it, and most won’t. They don’t want to give up whatever power they feel they do have, even if it’s just over their children.

In the meantime, there’s only this small attic room; a grey, chilly spring day outside; and whatever I do or don’t do with my portion of personal power this minute, this hour, this day. I will make choices to enhance or degrade the power of everyone I interact with, including myself. I’ll write, go swimming and pick up birdseed for our empty feeders. I’ll observe others, think about power and try to make mindful choices.

All content on this site ©2018

Jennifer Rose

except where otherwise noted